Tech needs better definitions

As the curtain fell on 2024, I had a baby. It was Friday the 13th, a date often associated with bad luck thanks to European superstitions stretching back a couple of hundred years. There is even a specific term to describe the “fear of Friday the 13th”: paraskevidekatriaphobia. Although urban legend actually has it that the shrink that coined it declared anyone who learned to pronounce it would be cured, which suggests a sense of humor (and reminds us how extra humans can be…).

And while my husband and I likewise noted the date as a humoress quirk, bad luck would, in fact, catch-up with us. Just five weeks later my Dad died. Baz Luhrman was onto something when he said the real troubles in life blindside you on an idle Tuesday afternoon.

Though he’d been ill for a while my father’s passing wasn’t expected, and I found myself in the strange and bewildering position of both gaining and losing a fundamental life force in such quick succession that it felt simultaneous. In the paperwork and aftermath, I occasionally confused my father’s DOD for our baby’s DOB. Those who have had similar experiences may relate to the feeling of being in some strange existential continuum, whereby it seems impossible that there wasn’t some kind of transfer. Like one Dr. Who fluidly regenerating into the next.

Now, I know my Dad wasn’t the Time Lord (alas), and I don’t think my baby is either (obviously I’m reserving judgment there…). Since they “met,” briefly – across 6,000 miles via FaceTime – shortly before my dad passed, I can conclusively rule out such a metamorphosis. But there is a kind of nonsensical comfort in imagining that at least some of his brilliance, kindness, and wit skipped over and found a new home with this new blank slate of a baby. That his unique and engaging essence persists.

But just as I was considering the nature of humanity, its composites and its complexity, I came across some Sam Altman commentary that I found particularly conflicting. For those that missed it, back in January the bombastic OpenAI CEO proclaimed: “My kid will never be smarter than AI” (cue frenzied headlines…).

It seemed that while most new parents were marveling at the miracle of new life and imagining possibilities, Altman was setting limitations and declaring that OpenAI’s artificial creation would always best his new biological one in the brain department.

This wasn’t framed as a prediction, or even a warning, but as a hope.

That’s right. Altman’s vision of a newly lobotomized humanity is a happy one, where removing the drudgery of –and responsibility for– applied intelligence allows each of us to make what he calls an “individual impact” that far outflanks anything we can do today. Yet the parts of us to be optimized and maximized for the greater good, the useful (but not very smart) remainder that is leftover once intelligence is outsourced, is left ambiguous. At least to me.

My intention is not to criticize Altman or his attitudes to fatherhood, or even AI. It is to suggest that reductive soundbites like his aren’t helpful. We need to get better at carving the distinction between external superintelligence and its advanced capabilities (where that exists), and those internal facets that are irreplicable and essential to the human condition and –I would argue– also consistent with the term “intelligence.”

We read about the first almost every day but, aside from occasional mumblings about “soft skills”, the latter is ill-defined despite the fact we’re urged to cling onto it as the AI avalanche hits.

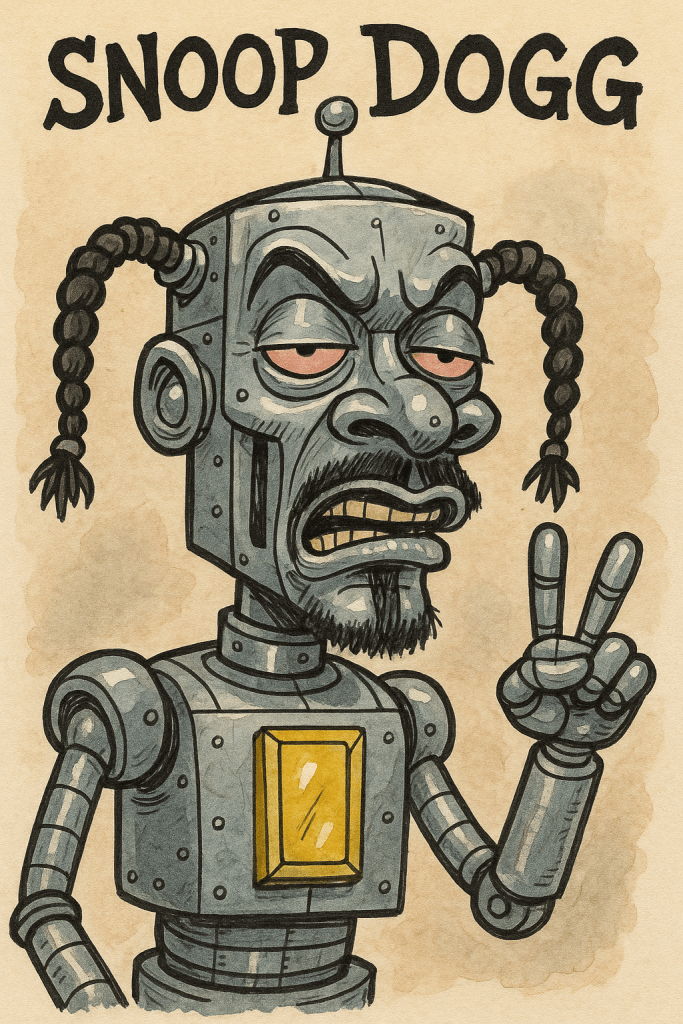

Attending the WSJ’s Future of Everything conference this week, less-smart-than-a-GPT film producer Brian Grazer made a successful –and amusing– attempt to explain the nature of that which cannot be captured, copied, and outsourced. Responding to a question on AI and creativity he used the example of Snoop Dogg.

“Could AI reproduce Snoop Dogg?”, he asked rhetorically. It could almost certainly produce a rapper with the same technical ability. But there is something beyond that proficiency that compels us towards artists, creators, humans. Grazer (who is producing a movie about Snoop) spoke about the rapper’s kindness and “heart” – his essence. The unique chemical mix of capability, lived experience, and personal characteristics that produces the lauded man himself.

Grazer is undoubtedly arguing that Snoop Dogg is smarter than AI. Would Altman disagree without caveat?

Yes, we are bound to live among intelligent systems that will lift away some of the cognitive work that humans have undertaken for millenia. In many cases, they will do that work at super speeds, utilizing more data than a thousand minds could process in a lifetime. But to compare mass regurgitation (however sophisticated) with the human condition and find the latter lacking seems to ignore an enormous and most significant part of the “smart” equation.

To deny, as Altman seems to be doing (though I doubt he actually believes it…), that there are extended moments of human brilliance that surpass the overarching impressiveness of his massive content machine reads as absurd.

While AI will be transformative for many purposes (even creative ones as it has already shown), I for one believe that each baby, each father, each paraskevidekatriaphobic and, of course, the one-and-only Snoop Dogg have something in common: a very human kind of intelligence which, for the sake of my child and Altman’s, we must strive to define and not flippantly malign.